UPDATE: This project has been replaced/updated with SonarMote. See this blog post for a more rencent implementation of what you see here. The alerts are now implemented as simple events on the Moteino Gateway.

Here’s another project I wanted to do for a long time. I wanted a sump pump flood warning alert system in place, for peace of mind when I’m gone from home for prolonged periods. For whatever reason I thought this was going to be more difficult but no, it’s almost as easy as pie!

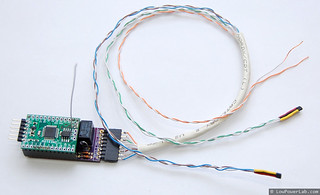

All I needed was a HC-SR04 sonar sensor and a USB 5V wall supply. The sensor only works at 5V so this method of powering the Moteino was very convenient since I already have an outlet close by for the sump pump.

The sensor has 4 pins clearly marked: VCC, GND, TRIG and ECHO. I connected VCC to VIN on Moteino, ECHO goes to D3 and TRIG to D4.

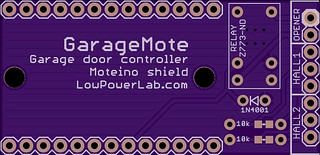

I used some of the code this instructable to get started and added my wireless code to handle packets and blink the LED and was done in no time. The setup was very simple, I estimated a good spot underneath the sump pump cover where there are no obstructions inside, cleaned it up, taped some velcro, secured the wires and that was pretty much it.

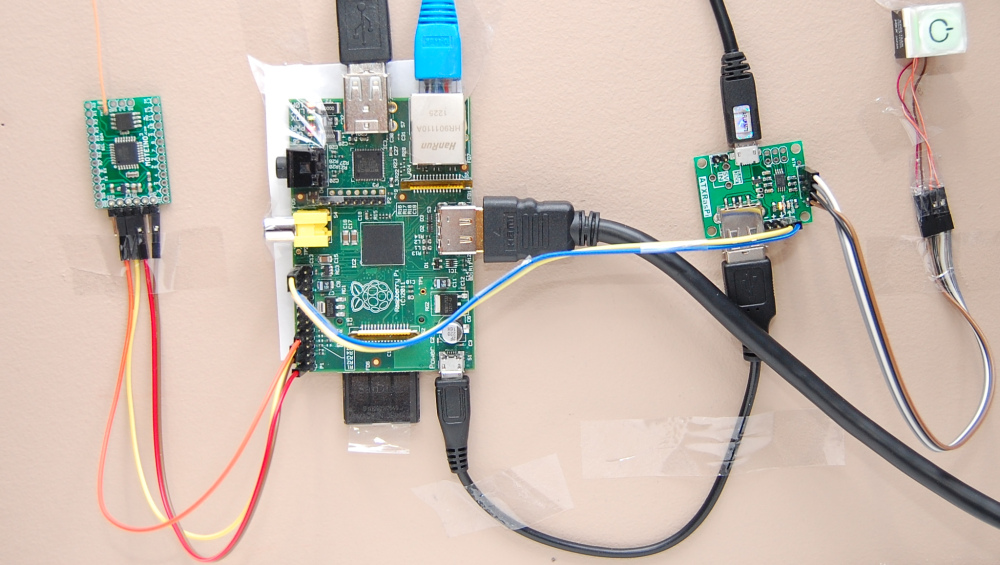

I added a few lines of code to my main Python script running on the RaspberryPi.

By the way, here’s how my RaspberryPi setup looks like, including the ATXRaspi power controller, the power button and the gateway Moteino (it’s an older R1 but just as good for as a gateway):

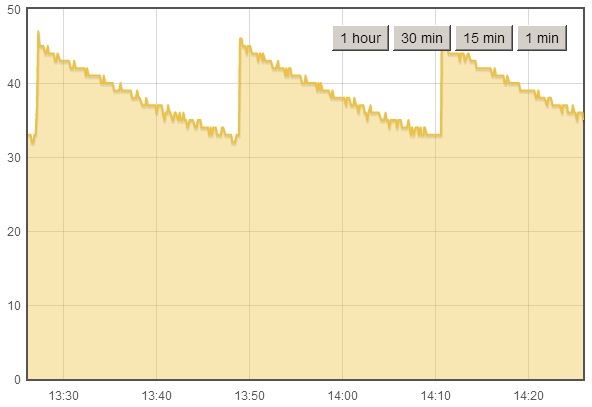

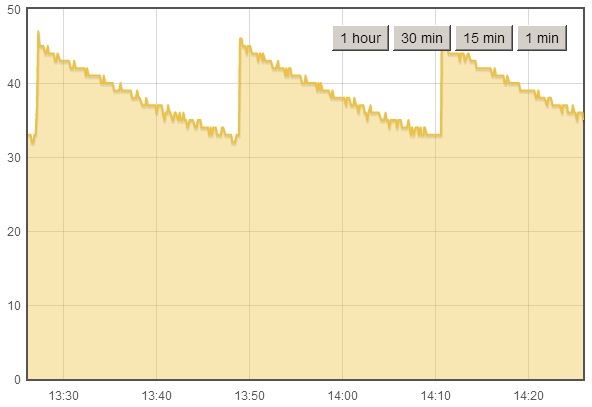

The Python script logs the data to EmonCMS and here’s a graph of how that looks like, the Moteino reports the distance to the water surface, so the spikes means the sump pump just kicked ON, and as water rises the distance decreases until the pump starts again:

It’s been a rainy spring so far here and I knew my pump kicks ON quite often, now I can see it in real time, and setup alerts if the water rises too much. Seems like the pump is always pumping water out when it rises to 32cm below basement surface. So setting an alert to something like 20cm below surface should be enough since I don’t expect the water to ever rise so much as long as the pump works. The alert code will send me a SMS message when this happens, here’s a test level, I set the live value at 20cm:

You can of course setup other types of alerts – like audio alerts or maybe a LED visual indicator (less useful when you’re not in your basement).

Fun/Scary fact: The sensor is very accurate even though there’s a variance of 1cm between some readings (resulting in a sawtooth graph) as water rises. Based on the graphs, how often the water is pumped (every ~23 minutes), and how big the reservoir is, I figured my sump pump removes roughly about 18.5 liters every cycle, or about 1158 liters (306 gal) every day, wow!

So now there’s an extra level of peace of mind when I leave on vacation. I guess being gone for even 1 day could mean disaster if the sump pump breaks down at the same time!

Time to think about how to gather/store all that water instead of throwing it away, after all, I pay something like $11 for every 1000 gallons of city water.

Source code is on GitHub: https://github.com/LowPowerLab/SumpPumpAlert